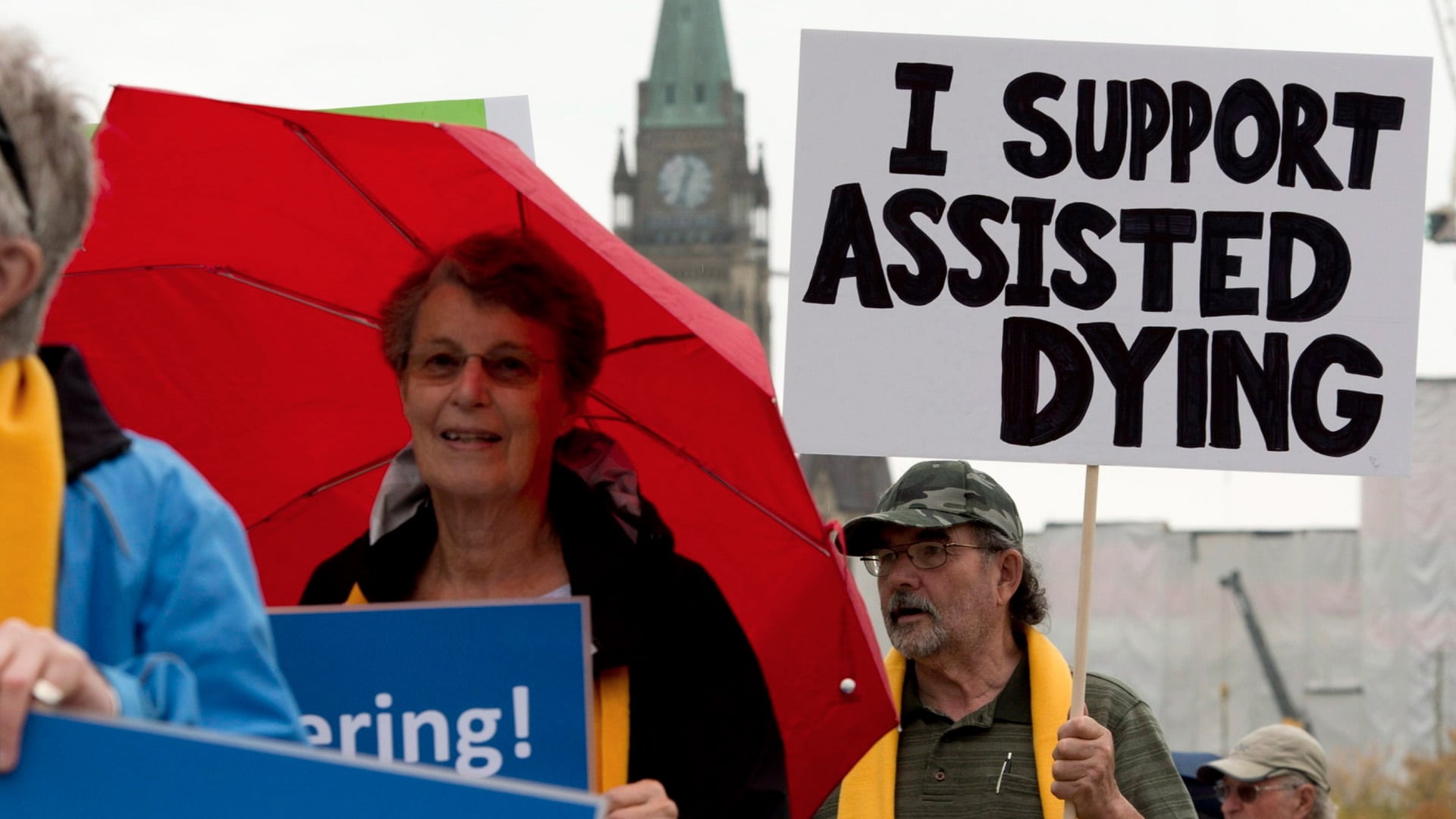

This past Friday, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously struck down the current laws against physician-assisted suicide, ruling that the laws prohibiting physician-assisted suicide infringe upon the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This is a divisive and historic ruling.

Our diocesan bishop, Charlie Masters has written a bold response to this verdict. I encourage you to read it thoroughly. Plenty of resources are supplied that will help you consider the ethical issues within a rich theological framework. Ultimately, however, Bishop Charlie is calling us to both prayer and action. As a community that is committed to seeing all spheres of our lives renewed by the gospel, including the social sphere, we must act. And as a community that places ourselves within the Anglican tradition and heritage, we must take seriously our Bishop’s command to act. In other words, both the gospel and our tradition do not permit us to sit back and see how things unfold.

But I would be lying to you if I said I was optimistic.

I’m not.

My feelings, however, don’t get to determine my actions.

As a Christian and a citizen, I will take action. I will pray diligently and take advantage of the means that are available to me within our government’s structures. I will also provide opportunities for our community to get engaged. We find ourselves at an impasse as a country, and, even if we don’t feel overly hopeful about this situation, we must take action. In addition to the public and corporate action that Bishop Charlie calls us to take, I want to offer two things for us all to consider:

The first is civility.

Richard Mouw calls Christians to embrace a “convicted civility” (I’ve written about this over at Relevant Magazine regarding disagreement among Christians, but it still applies to our engagement in the public sphere). As Biblically faithful Christians, we carry strong convictions about the issue of physician-assisted suicide. But what we believe is always coupled with how we express what we believe. And what we believe can be seriously compromised if how we share it does not reflect Christ.

We must choose to be civil in our dialogue, because without civility our conviction just comes off as belligerence. Christian civility means a commitment to listen before speaking, to understand differences rather than trivializing them, which means we must deal with people’s real concerns rather than building straw-men arguments. We must humanize rather than demonize those we disagree with. After all, if we dehumanize a person we disagree with while arguing for the inherent value of every human life, we’ve betrayed the point we’re trying to make. Instead, we work within the tension of holding a posture of convicted civility, while not diminishing the significant and very real disagreement. We can be gentle and generous towards others while remaining firm in our own convictions. If we do not respond with convicted civility, we will inevitably misrepresent the gospel.

Civility, when it comes to physician-assisted suicide, is of the utmost importance. Because we all have friends and family who are celebrating this decision. I know that I do. We don’t share the same perspective or theological convictions. And when I take the time to listen, this isn’t about abstract propositional truth. This “issue” involves heartbreaking stories of family members dying too soon, in tragic ways. This is fundamentally about people who were and are loved, whose lives are ending in pain and suffering. If our convictions cause us to bulldoze over people’s experience of grief and loss we have completely missed the mark. If we cannot extend compassion and mercy to the experiences that shape convictions different than our own, it is to our own detriment and due in no small way to a lack of understanding of the gospel.

If we take a posture of convicted civility, we may actually find a small patch of common ground. Within a humanistic, utilitarian worldview that says, “We need to eradicate and avoid suffering as much as possible and focus on living in our prime with health,” the support for doctor assisted suicide is an attempt to be merciful and compassionate. Can we affirm this desire for lives marked by compassion and mercy as a starting point for the conversation? Yes, we all want to see mercy and compassion when it comes to pain, suffering and death.

But the foundation from which we approach the issue of death (and life) differs. For us, it’s not the secular vision of individual rights that provides a foundational understanding of human life. It’s the gospel that shapes how we see life in this world, and as a result, life has inherent value because we are made in the image of God. The gospel affirms (even if sometimes uncomfortably) God’s authority to create, sustain, and bring an end to life. As Christians, we see the expression and embodiment of mercy and compassion in the face of death taking place in a far more dramatic and different way. Although many things have tarnished and distorted the image of God within us, we see that God endures great pain and suffering so that life may burst forth out of death. The merciful and compassionate death that we all desire has already taken place upon the crooked beams of the cross.

No law can rob Christians of their ability to proclaim the gospel in the midst of their deaths. Death and suffering do not rob us of dignity. Because the gospel has defeated these things.

If you want to start thinking theologically about the issue of death, let me suggest 2 Corinthians 4:7-18. St. Paul writes, “We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus.” While Paul is talking about the suffering and toil he faced in proclaiming the gospel, he understood that in his suffering he carried a death that had already taken place: the death of Christ. And in doing this, Paul concludes, “so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies. For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus also may be manifested in our mortal flesh. So death is at work in us, but life in you.” Death is at work in us, but because of a merciful and compassionate death that took place for us, life is actually at work within our death. Even if we’re afflicted and crushed and perplexed by our suffering, these things cannot overcome what Jesus’ death has accomplished for us.

What’s the implication of Paul’s theology of death and suffering? It brings me to the second consideration I want to put before you:

We are invited to die well.

The tides of culture could very well change dramatically over the next few years. By the time my daughter is an adult, physician-assisted suicide may be a normal reality in Canadian culture. Regardless, every Christian will die. But death for us is an opportunity for the gospel to live. As St. Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 4:16-17, “We do not lose heart. Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison.” Don’t misunderstand Paul. The affliction may be serious. You may die from a terminal disease that robs your body of any strength, or a disease that takes away your mental capacities. The affliction may be horrid. We cannot downplay that. But in view of what awaits us? It is a light, momentary affliction.

If we carry the gospel in this way, if we choose to die well — we will actually be powerfully demonstrating the gospel. No law can rob Christians of their ability to proclaim the gospel in the midst of their deaths. Death and suffering do not rob us of dignity. Because the gospel has defeated these things. Our dignity cannot be robbed because our dignity isn’t found in our health or strength. Our dignity is in the fact that we are image bearers of God, and that this image is being restored in us because of Christ’s death and resurrection; and death is ultimately the way in which we will enter fully into the glory that awaits us — the reality where suffering, pain, sickness, and death are no more.

I understand that I write this admonition as a young man in his prime. I realize that in the course of time, I may have to put these very words into action. But we must understand, that if the cultural tide changes, our most powerful witness will be in how we die. How we die in light of the gospel challenges our culture’s perspective of dying. It actually offers a far better vision of death. No matter how we die, we will die with dignity and hope and life that cannot be robbed by the tragic powers of suffering and death.

As we get engaged in this public issue as a community, please carry a convicted civility. We must recognize that those who are passionate about seeking mercy and compassion extended to those who are suffering are actually tapping into a deep desire for the grace of Christ. We must carry our convictions not just in how we attempt to shape the public sphere, but within our own lives. The gospel forms how we approach pain, suffering and death. Death, suffering and pain no longer have the power to rob us of dignity. Because in his crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus has robbed these very things of their power.