Ask a Vancouverite what they like about living here and you’ll get some pretty standard results — perhaps the top being “Where else can you ski and go to the beach on the same day?” Many places have beaches, and many places have mountains, but few places have both. As much as I love the ocean, the mountains have always been my favourite.

Growing up in the city, the mountains were not only a beautiful sight to see (in my family we refer to the first sunny, clear day of winter after a fresh snowfall as “Aaaahhh Day”), or a fun place to play. The mountains are the anchor my geography.

The best piece of Vancouver specific advice that my parents gave me (aside from don’t forget a rain jacket… that one has served me well) was one simple phrase: The mountains are north. With this one phrase, I was given an automatic way of orientating myself when I was lost. With Vancouver’s grid pattern street layout, I could walk to a corner, find the mountains and basically have a big red YOU ARE HERE dot on a map in my mind. The mountains are my north star in the daytime, and my compass when I have none.

Some time in my late high school years I remember a friend from youth group shared a reflection on Psalm 121. He calls it his BC Psalm. It begins, “I lift up my eyes to the hills. From where does my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth.” The promises in this Psalm, of the Lord watching over us, not letting our feet be moved, or the sun harm us by day, were especially appealing to him in relation to a recent hike he had been on, and to me based on my pale skin tone. But for years this memory has stuck in my mind, and when I lift my eyes and look to the mountains — to find my way, or simply to marvel — I am reminded who made those hills and that He is the source of my help.

But not being able to see the mountains, or not having the benefit of a gleaming sunset or fresh dusting of snow to draw my eyes to their beauty doesn’t erase them. They are still there. They are still north.

For me there is something poignant about how these ideas converge. The way the mountains orient and awe me, and the way Psalm 121 portrays God as the almighty creator, helper, and protector. There is a power in the junction of this image of the mountains, and the way the Psalmist lifts his eyes to them and how they remind him (and me) of God.

The romantic poets were keen to observe and write about nature. A key concept for them was the sublime – a powerful, awe-inspiring beauty. Percy Bysshe Shelley writes of Mont Blanca, in the magnificent French Alps:

Mont Blanc yet gleams on high:—the power is there,

The still and solemn power of many sights,

And many sounds, and much of life and death.

For Shelley, this mountain was more than a mountain. In contained a still and solemn power, and somehow, someway, much of life and death — the very stuff of existence.

For the original audience of Psalm 121, the hills were more than hills too. God brought Noah’s ark to rest on a mountain. He intervened in Abraham’s life and showed mercy to him and his son Isaac on a mountain. God gave the law to Moses on a mountain. The temple in Jerusalem was built on a mountain.

But, despite their sublime beauty, and the historic signposts both secular and sacred, I have to admit that I sometimes don’t see the mountains.

Perhaps this is a function of me growing up here in the city and my familiarity with the landscape having a numbing effect. Or maybe it’s a cloudy day, and I legitimately can’t see the mountains. But not being able to see the mountains, or not having the benefit of a gleaming sunset or fresh dusting of snow to draw my eyes to their beauty doesn’t erase them. They are still there. They are still north.

In the same way, even if we turn a blind eye to God, it doesn’t change the fact that he is the Almighty Creator, our Helper, our Father who protects us. These things are constant despite our inability or unwillingness to see them, and regardless of how we’re feeling.

In fact, Christ’s ultimate intervention into human history happened when everyone had turned their backs on him when he was completely forsaken. And guess what? That happened on a hilltop also. Christ’s sacrifice on the cross covers all the times we are forgetful and unseeing, all the times we turn our backs on God, and refuse to orient ourselves to Him. This is God’s supreme act of love. While we had our backs turned on Him, He died for all the times we had and would forsake him. While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

Let’s let this mountaintop moment orient our lives. Let’s let this be our true north. When we look to the Mountains, let’s not just see them as beautiful geological forms or places to hike and ski. Let’s not simply see them as sublime like the romantic poets. Let’s look to the mountains and remember that the crucial help for humanity comes from the Lord, comes from Jesus our Saviour. It isn’t dependent on the weather, or us remembering, or seeing, or orienting ourselves properly. It is a constant, and in that there is grace.

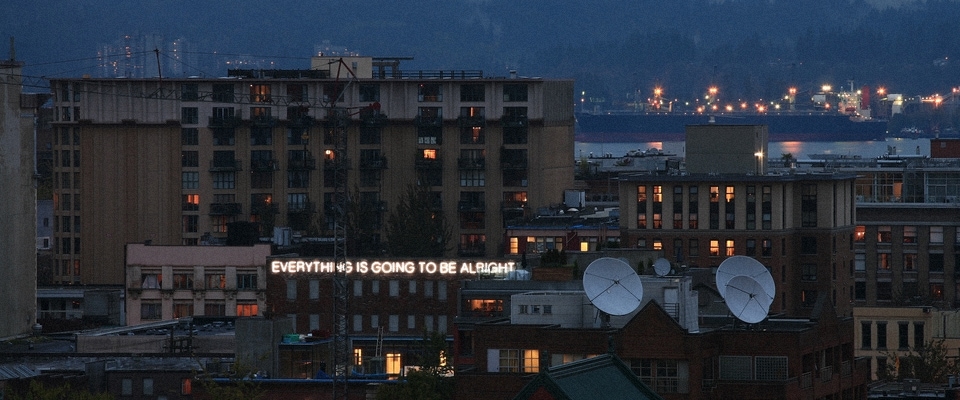

Photo: Gord McKenna: Vancouver New Years Eve 2010