Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light. (Matthew 11:28-30)

Jesus’ words from the verses in Matthew above have always had a tinge of the pastoral for me. Maybe it’s because the favourite way to explain the concept of a yoke is in relation to livestock on a farm. For me, this explanation evokes the restful imagery of an English countryside, where farmer has taken a break beneath a shady tree in the middle of the afternoon to eat lunch, and feed the crusts of his sandwich and the scraps of his apple to the team of work horses that pulled his cart through the field. Like a scene from Babe or a modernization of the setting of Psalm 23.

But often we forget that weight is distributed across a yoke, so even though Jesus promises us an easy yoke and a light burden, this does not come without strain or effort at all. Imagine a Clydesdale and miniature pony pulling a heavy cart. The fact that the miniature pony cannot physically pull as much weight as the Clydesdale, does not change the weight that they are hauling. If anything the strain required by the Clydesdale to move the cart is much more.

When Christ says my yoke is easy and my burden is light, he is not talking about the yoke that he wears, but rather the yoke he gives to us. The cost of our easy yoke and light burden is put on Christ. Christ’s yoke was anything but easy and light. But taking on that weight by himself was what was necessary for freeing us from the burden of our sin.

Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows;

yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. (Isaiah 53:4)

Jesus fell under the weight of his cross, which cannot come close to comparing to the weight of our sin which he bore.

Another way that the concept of a yoke is explained and understood is in relation to slavery. Being under the yoke of slavery is something Paul talks about in Galatians 5. This is not a metaphorical understanding, for Paul or for us. Throughout the past, and even in horrific situations in the present, slaves have often been bound one to another by shackles or a yoke around their neck, treated worse than animals or criminals. This troubling image is much more like the yoke that Jesus took on for us.

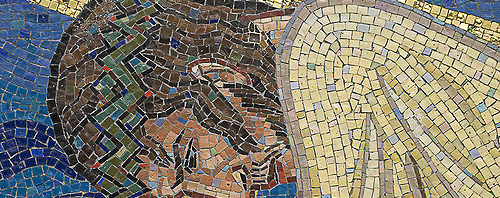

Jesus became both an animal (as a sacrificial lamb), and a criminal (dying a convict’s death on a cross). And his yoke was heavy. Jesus fell under the weight of his cross, which cannot come close to comparing to the weight of our sin which he bore.

Our pastoral view of the yoke is incomplete. It cannot exist without Christ’s humbling of himself, his submitting to a criminal’s death, his being led like a lamb to the slaughter. Later in Matthew, Jesus says “whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” Christ becoming a servant, becoming a slave, ransomed us from our slavery to sin. His sacrifice provides our freedom, his suffering ensures our peace.

I feel the pastoral peace evoked by Christ’s call for the weary and heavy laden to come to him most on my sabbath – a day mandated by God to be set aside for rest in him. On my sabbath, I’ll often go for a walk at the beach, or end up sitting in a coffee shop or having a good meal with good friends. These things restore me and are truly gifts from God. They are easy and light and full of joy. But the cost for me to have the true freedom to enjoy these things and enjoy the peace of God and true Sabbath rest was burdensome and sorrowful and afflicting.

During Lent, as we look towards Springtime and Easter, as we enjoy our Sabbaths and the gifts that God has for us, we also remember the pain and effort required to take away the weight of our burden of sin. A weight so great that it crushed Jesus, and he fell beneath it.

Stations

During the weeks of Lent, St. Peter’s writers are reflecting on the Stations of the Cross. These fourteen moments from the last days of Jesus’ life offer us an opportunity to consider where we would have been in this story – in the crowd? Waiting in the courtyard? At the foot of the Cross? It’s our prayer that you will find these posts meaningful food for thought over the next few weeks.