Several weeks ago, I had a rare opportunity. My hands were shaking with anticipation as they handled a first-edition, English language Bible. Truth be told, I wasn’t all that familiar with this text—and its significance—before I providentially entered its keeper’s office. On the assumption that this version of the Bible is also unfamiliar to you, let me offer a brief introduction.

The History of the Geneva Bible

The Geneva Bible, says one scholar, was “the Bible of the Protestant Reformation.” It was produced some 50 years before the King James Bible (which is more well known). In its time, the Geneva Bible was widely circulated and used, remaining popular long after the King James translation was released (1611). As to its origins, the Geneva translation is linked with English refugees living in Switzerland as a result to Queen Mary’s persecution of Protestant Christians. These exiles took on the task of translating the Old and New Testament into their common language (as opposed to Latin). The project was superintended by John Calvin, John Knox (of Scotland), and other Reformers. It represents the spirit of the Protestant Reformation, with its emphasis on reverent, focused, and understandable engagement with the Holy Scripture.

To be sure, the Geneva Bible has an impressive usage history. It is quoted hundreds of times in Shakespeare. 90% of the King James Bible translation derives from it. And, the Geneva Bible was the first to be brought to America. The trivia list goes on and on. In introducing the Geneva Bible, however, my focus lies elsewhere.

How to Read What We Read

The Geneva Bible offers some valuable lessons about reading the Bible well. These are lessons that are worth heeding. They are lessons that are all to easily forgotten.

In discussing the church’s use of the Bible with some of my Roman Catholic friends, I have heard a familiar charge on more than one occasion. They allege the Protestant Christianity is dangerous because it makes people think that they can read and interpret the Bible without any help. In other words, Protestant Christianity is spiritually reckless because it leads people to think that any way they would read and interpret Scripture is trustworthy and valid. Such a tendency, argue my friends, results in interpretations of the Bible that are whimsical, simplistic, prejudicial, and theologically unsound.

To be sure, the contemporary North American scene demonstrates that there is some truth in these indictments. In my own experience, I have come across a number of bizarre and faddish modes of biblical interpretation. But is this phenomenon the intended outworking of the Protestant Reformation? Are subjective, highly individualized ways of reading Scripture what the Reformers had in mind?

The Geneva Bible represents the spirit of the Protestant Reformation, with its emphasis on reverent, focused, and understandable engagement with the Holy Scripture.

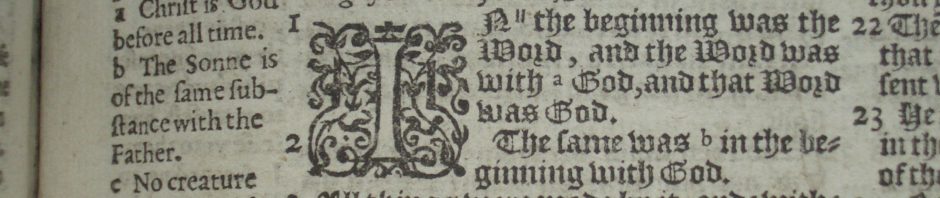

According to the Geneva Bible, the answer is no. It’s a firm no. This is the main lesson I learned from exploring the first edition which was in my hands only days ago. This lesson did not come to me from the scriptural content of the Bible, so much as from the details of its layout. Let me explain.

In the first place, the Geneva Bible contains verse numbers. We take this for granted…only because it was introduced, for the first time in English, by the Geneva Bible! The insertion of verse numbers are highly consequential. You don’t need verse numbers to read the Bible alone. Rather, they are an essential organization and tracking tool for the communal reading of Scripture. In short, the placement of verse numbers are telling: for the Protestant Reformers, the interpretation of Scripture was not to be an isolated, subjective, “me-and-Jesus” endeavour. To be properly interpreted, Scripture needs to be read in the church, in conversation with other Christians.

This same point is taken to a whole new level by another feature of the Geneva Bible: the placement of commentary notes in the margins. The Geneva Bible—the Bible produced for the average Bloke & Sheila to read!—is a study Bible. And this study is to be guided by the church’s theological and biblical teachers, past and present. In other words, when you encounter a difficult passage, you are intended to consult the “Christian tradition” (represented by the margin notes!) in discerning its proper meaning. Our imaginations are not to operate in fanciful and unbounded ways in our reading and understanding of Scripture! Put another way: to read the Bible in a trustworthy manner, the Christian does not merely need to know how to pronounce the English alphabet. She also needs to be informed and formed by prior Christians and present original-language specialists.

One final observation warrants attention. In many printings of the Genevan Bible, a catechism would precede the actual Scriptural texts. A catechism is a concise statement of the Christian faith, assembled not by any single person, but rather by a group or council of church theologians. The Nicene Creed, which we Anglican’s cite most Sundays, is catechetical in nature. It provides a short-form summary of the basic message of the Bible. The inclusion of a catechism on the front end of the Genevan Bible sends a decisive message: the Old and New Testaments are to be read in light of the catechism. The catechism, in turn, was derived from the Bible, put together by people who have devoted considerable, seasoned study to the text and to the running Christian theological tradition.

At first sight, the thought having our reading “guided” can be a bit off-putting. We’re an individualist people and we see tradition as a hindrance to truth. But that is not how the Protestant Reformers saw it. In contrast, they saw the church’s tradition—and its present existence—as a means for illuminating the great truths of Scripture. This is why the Genevan Bible has verse numbers, margin notes, and a preliminary catechism.

If contemporary evangelical Christians seem far removed from such an attitude, its not because they are products of the Protestant Reformation. Its because they’ve deviated from it. In this department, I think we could all use a bit of convicting. Let’s start reading together—with the church past and present—so that we will read well.